Ten Principles of Good Design Redux | Part 4

Monday, August 8, 2011

Good Software Design Makes a Product Understandable

Friday, August 5, 2011

Replicator Wars | Consciousness as War Machine

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

C++ : The Resurrection

I have always had a love-hate relationship with C++; it gives you almost total control over the hardware but requires that you be very mindful of that hardware. It has been a very long time since I wrote any C++ code in anger, and until yesterday I was convinced that I would never write another line of C++ in my life. Then I read an article in the most recent MSDN Magazine on Windows API development with the latest version of the C++ standard, whose working title has been “C++0x”, and will officially be known as “C++2011”. I have been aware that there was a new reversion of the standard in the works, but I had no idea how significant a step forward this latest revision is going to be. Lambda Functions, Type Inference and a “foreach” equivalent in C++? Who are you and what have you done with C++?!?

And there is a lot more to the new standard, which is now final, and should be published some time this Summer. I found this Channel9 interview with Herb Sutter; he gives a very good overview of the new features of C++2011, the process that brought it into being, and what it means for developers targeting the Windows Platform.

I think I am going to have to give C++ another chance, though I don’t know what this is going to mean for the other languages that I have been using recently; F#, IronPython and Scala? I guess we will just have to wait and see.

Thursday, July 28, 2011

Good Software Design is Aesthetic

Ten Principles of Good Design Redux | Part 3

I usually get rather testy when software developers insist that Software Development and Architecture are more Art than Science. The testiness is usually exacerbated by the poor quality of the code that is generally written by these very same software developers. If you need to do a depth-first traversal of a binary tree it is extremely unlikely that you will need to invent a new algorithm for doing so. Somewhere in the Noosphere you will undoubtedly find an exhaustive academic study on optimal algorithms for tree-traversal. I have lost track of the times that I have had to scold developers for attempting to implement their own crypto or thread-synchronization primitives.

Is traditional Meatspace Architecture an Art or a Science? It is unarguably a creative discipline, but it is fundamentally underpinned by the material sciences and psychology*. Buildings that do not respect the laws of physics don’t stand very long, regardless of how beautiful they are. Meatspace Architecture is a creative process that is governed by a set of predominantly invariant constraints. It is true that new materials are constantly being invented, which alter those constraints, but I don’t imagine gravity is going away any time soon (until we start living in space anyway). I believe that Software Architecture (in the small and large) is no different from its Meatspace namesake.

So now that I have pooh-poohed Software Development and Architecture as Art I am going to do some legerdemain, some prestidigitation, and apparently contradict myself. Great Software Architecture is Art! A great software design, either in the small or large, can, and must in my opinion, be a thing of beauty. As a Software Architect you must be able to show a design to a colleague and have them say “Wow, that is awesome!”; “awesome” being equivalent to “beautiful” in High-Geek.

Is it not true that budding artists of all types spend years and years learning, and in some rare cases developing, formal techniques? Only when they have truly mastered these techniques do they go on to create truly magnificent works of art, channelling their raw creativity and talent through a set of deeply inculcated techniques. Yes, yes, I know there are some great works of art painted by cats, but they are the exceptions rather than the rule.

And there is great hidden value in creating aesthetically pleasing software designs. The human brain is genetically tuned to recognise certain levels of complexity and other naturally occurring patterns as either aesthetically pleasing or not depending on their utility. By ensuring that your designs are aesthetically pleasing you are tapping into a pattern recognition system 2.5 million years in the making. An aesthetically pleasing software design is going to be more understandable, more enjoyable to implement and maintain, and most definitely easier to sell to a client or your management.

Quod erat demonstrandum (I hope anyway).

* Historically psychology has been considered a pseudo-science but I think folks like Steven Pinker and his ilk are dragging it kicking and screaming into the realm of “pure” Science.

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Good Software Design Makes a Product Useful

Ten Principles of Good Design Redux | Part 2

“Of course software makes a product useful! Software is useful by design!” I hear you say. But is that really always the case?

At the beginning of this year I received a Blackberry smartphone from my employer. It was not one of the current-generation touchscreen devices, and I can’t speak directly to how useful those devices are, but the device that I received was not useful in the least. The combination of the form factor, the trackball input device and the very poorly designed user interface rendered the device practically useless to me. Despite the fact that this was a paid-for smartphone, with both voice and data covered, it sat in my bag unused for months. I eventually just sent it back and decided to cover my own communication costs rather than be subjected to the Blackberry user experience. I never even bothered to find out the model number, but it looked something like this.

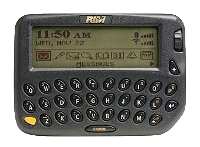

I do know people who swear by their RIM devices, but I think RIM’s recent poor performance speaks in part to their inability to design and ship useful devices; this is the company who shipped a great tablet platform hobbled by its dependency on a Blackberry smartphone to enable its PIM features. And the sad thing is, there was a time when they were thought to be the embodiment of “useful”; I recall getting a Blackberry pager when I first joined Microsoft Corp. in 2000. It looked like this.

It became the most useful piece of technology I owned. So what happened between then and now? The form factor of the phone that I found unusable in 2011 was the logical evolution of the pager that I found indispensible in 2000.

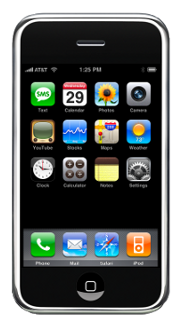

This happened.

And the iPhone reset the “useful” bar. Dieter Rams is a huge Apple fan, and so am I. I want to quote the description of Rams’ principle as it appears on Wikipedia because it so precisely describes Apple’s apparent approach to designing useful products.

“A product is bought to be used. It has to satisfy certain criteria, not only functional, but also psychological and aesthetic. Good design emphasises the usefulness of a product whilst disregarding anything that could possibly detract from it.”

When I use any feature of my iPhone I can visualize the team of designers and engineers brutally redesigning and refactoring that feature to make it as useful to the user as possible. Though RIM’s devices are functional, they were clearly not designed to be beautiful and give their users a deeply satisfying visceral experience. And though there are things about the iPhone that bug me, for example the lack of ability to “skin” the user interface, they do not detract from the overall experience, because it is just so bloody great!

As an aside, I recently saw Microsoft’s new mobile operating system, codenamed “Mango”, running in the wild. It is beautiful. That is not a word that I use to describe Microsoft products very often, but it is totally apropos in this case. Though the predominantly monochromatic tile user interface metaphor is very bold, it is offset by a number of subtle visual elements and the Metro typography, which makes the whole experience highly pleasing, usable and ultimately useful. There is definitely a Windows Phone in my future.

I think Rams’ “useful” principle is applicable to far more than just User Interface and User Experience Design; Software Architects should deeply consider the usefulness of the technology that they design and build, even if that software has no user interface to speak of. Software should ultimately always be designed with the actual living and breathing humans who are going to be affected by it, not just use it, in mind. This is the core principle of Gestalt Driven Development.

Good Software Design is Innovative

Ten Principles of Good Design Redux | Part 1

If I were to propose a software system design based on a 40-year-old model for distributed computing, i.e. a classic 2-tiered Client/Server Model, would that be a good design, even if I used current technologies, e.g. the .NET Framework 4 or the latest JDK?

The case can be made that innovation is motivated by a company’s financial and competitive umwelt. That is definitely true, but I would assert that this is an effect rather than a cause. I believe that humans are driven by an innate instinct to improve and optimize our tools to maximize our survivability as a species. That is not to say that all innovation always moves us forward; some innovation can be positively retrogressive in the context of the survivability of our species. On the whole though I do believe that innovation moves us, in the large, to a better place. And innovation in software technology is no exception.

So to answer my earlier question; there might be some very niche cases where a design based on the classic 2-tiered Client/Server Model might represent a good design, but in general I would assert that it would not. Having tested the model thoroughly over the last 40 years we have discovered its obvious, and even subtle, flaws and weaknesses and have innovated new and improved models to address those shortcomings. The case can also be made that the problems that we are trying to solve have themselves significantly evolved and mutated, and that the old models have limited to no utility in light of these transmogrifications.

One of the most glaring limitations of the classic 2-tiered Client/Server model is that software designed using this model does not age well; because of the typically high degree of coupling between the domain and presentation logic, it becomes more and more difficult to modify the application as it ages, and it makes replacement of the user interface technology almost impossible. The model seems to have a innate “drag” that accelerates the accrual of technical debt over time, inevitably leading to the technical bankruptcy of the system or application.

To be clear, I do not espouse innovation for innovation sake, or using emerging software technologies just because they are new. I do espouse keeping one lazy eye on the bleeding edge of innovation, and always considering how these emerging technologies might simplify or improve an application or system.

Ten Principles of Good Design Redux

A few weeks back I wrote a teaser about Dieter Rams’ “ten principles of good design” and mentioned that I believe these principles are very applicable to Software Architecture. I did not however elaborate on how these principles are applicable. I hope to address that with a number of posts over the next few weeks, each covering one principle. I will endeavour to not deviate too far from Mr. Rams’ original definitions, given their recursive elegance, but in some cases I will need to invoke Poetic Licence.

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Now This is Visual Debugging!

Yesterday I installed a novel Visual Studio debugging tool from Microsoft Research and Brown University called Debugger Canvas. I started playing with it and was immediately hooked; now this is visual debugging! Debugger Canvas augments the default debugging experience in VS and gives you an interactive visual graph showing the call stack stack and code path. Each node in the tree contains the source code for each function. It even respects your font and layout preferences!

As you step through the code, the active line is highlighted as usual, and “Step Over” and “Step Into” also work as you would expect; if you step over a call, a new node is not created. Once a function has been stepped into it remains on the canvas even when the call returns, building up a visual representation of the code path. All the regular VS debugging windows and features work as expected, e.g hovering over a variable will show its current value.

Another cool feature is the ability to take snapshots of the value of a variable and then optionally display that on the canvas as a visual history. You can also annotate the canvas with “sticky” notes. The canvas itself is a file so you can save it for later use or you can save the file as an XPS document. I can imagine that test engineers will love this; it will allow them to reproduce a defect and then capture the full code path, pertinent variable history and their annotations, and then attach the resulting document to the bug in their defect management system.

There are a bunch of other features, including a “trial feature” that allows you to edit the code directly on the canvas (though apparently the code is a little buggy still). If during a debugging session you tire of Debugger Canvas you can just open a source file and continue debugging using the default debugging capabilities of VS.

I hope Debugger Canvas makes it into the next release of VS. You can download Debugger Canvas from Microsoft's DevLabs site.

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

A Love Affair with F# : Embracing a Functional Style

I grew up drinking the Object Oriented Kool-Aid, which imbues the drinker with the idea that functional programming languages are arcana whose use and utility are limited to academia and programming language research.

Despite this I remained vaguely curious about functional programing (probably because I secretly suffer from “academic envy”), and every so often would do some informal research on cool functional programming language constructs; closures, continuations, monads, list comprehension, higher-order functions and pattern matching being good examples. I was eager to use the aforementioned in anger but I never had what I thought was the “killer app” for a predominantly functional language.

Note: I say “predominantly functional” because many modern functional programming languages are not purely functional. For example F# is a best-of-breed functional programming language, with object oriented features. In comparison C# is a best-of-breed object oriented language that has functional programming language features. F# and C# seem to be slowly converging.

Another reason that I did not make a serious foray into functional programming was the lack of good tools. I tried my hand at Standard ML, but since I had been so spoiled (in a good way) by Visual Studio, I could not bring myself to go back to a generic text editor and the command line. I was also not happy about the prospect of having to learn yet another set of APIs.

In 2005 Microsoft Research released F# 1.0 into the wild. F# is in the ML family of languages, so the little knowledge I had acquired playing with SML was applicable, and F# is a native .NET language, so I was able to leverage all of my existing knowledge of the .NET Framework. Initially the Visual Studio integration was very limited, but improved steadily with subsequent releases of F# and Visual Studio. When Visual Studio 2010 was released along with F# 2.0, F# finally became a bona fide 1st class .NET language. So with the release of Visual Studio 2010 I officially ran out of excuses for not learning and using functional programming.

I had played with F# before the VS 2010 release but my code always landed up looking very C#-like, with ref and mutable keywords all over the place. I miserably failed to embrace a functional style, and therefore missed the real magic offered by functional programming.

I recently wrote what I would consider my first “real” functional program using F#. I decided to port an InfoPath/SharePoint/Excel(VBA) application to .NET and provide a number of enhancements in the process. I also thought it was a good opportunity to use functional programming in anger, so I decided to write a couple of the modules in F# and embrace a functional style from the outset. This meant writing the code as a hierarchy of functions, avoiding side effects and mutable types unless necessitated by the use of existing non-functional .NET APIs, and making as much possible use of F# types, e.g. Lists, Tuples and Records, and F# language constructs, e.g. Active Patterns.

One of the modules that I wrote was a deserializer for InfoPath XML forms, which uses Partial Active Patterns to parse the XML. I will describe the implementation of the deserializer in detail in a future post.

I am not sure when it was that I achieved Functional Programming Satori; perhaps it was around the thousandth line of F# code; but it was profound and left me with a lingering love for F# and functional programming in general. There is something about functional code that is just so bloody elegant! I excitedly showed my F# code to a colleague, not because I wanted him to review it for correctness, but because I wanted him to appreciate the aesthetics of it! And that aesthetic appeal did not come at the price of performance; the resulting code performed as well as an imperative C# implementation that I had written as a benchmark.

I highly recommend learning and using F# to all software engineers actively developing on the .NET platform. For those developers who have mastered LINQ they will find that many of the concepts they have learned will translate directly to F#. You can find everything you need to know to get started at the Microsoft F# Developer Center.

For those developers who are developing in Java I recommend taking a look at Scala. It is a general purpose programming language that includes many functional programming elements, and targets the Java Virtual Machine. Scala is what Java might have become if it had not been hobbled by politics.

Be warned though, once you have learned functional programming you may never want to go back!

Thursday, July 7, 2011

Ten Principles of Good Design

A few years ago I learned about Dieter Rams’ ten principles of “good design” and was immediately struck by how applicable these principles are to Software Architecture. I recently watched an amazing documentary film by Gary Hustwit called “Objectified” which is about “our complex relationship with manufactured objects and, by extension, the people who design them”.

This clip from the film, in which Dieter Rams talks about his design principles, and a recent discussion I was part of concerning whether one should optimize for making a product “perfect” or for meeting committed ship dates, reminded me of how rarely products, including software, are designed using these principles. This film should be required viewing for all Software Architects.

Note: Gary Hustwit made another excellent documentary film called “Helvetica” which is a must see for anyone doing user interface design.